Introduction: Why an Ancient Object Still Speaks

Across millennia, cultures, and belief systems, few symbols have retained the psychological gravity of the Ark of the Covenant. Often reduced in popular imagination to a mystical relic or cinematic artifact, the Ark is far more enduring and far more relevant than myth alone would suggest.

Psychologically, the Ark functions as a symbol of containment: a sacred structure designed to hold law, memory, authority, and power without allowing those forces to become destructive. Long before modern psychology, systems theory, or trauma science had language for regulation, the Ark encoded these principles symbolically by warning that power without containment corrodes individuals, families, and civilizations.

This blog explores the Ark not as a religious curiosity, but as a psychological and systemic blueprint that speaks directly to family systems, ethical leadership, trauma-informed institutional design, and why uncontained systems inevitably collapse.

A Brief History of the Ark of the Covenant

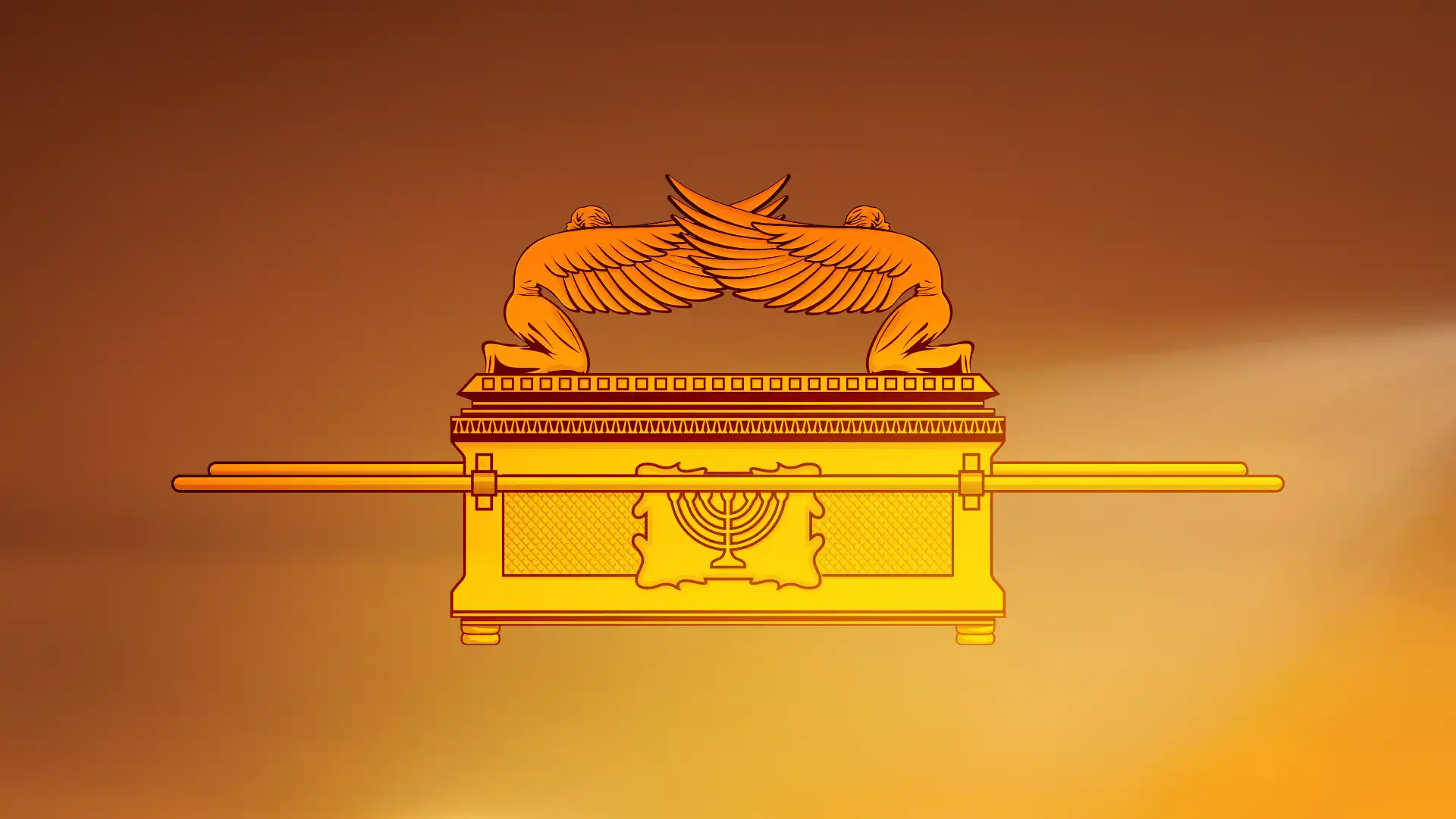

In Hebrew scripture, the Ark of the Covenant is described as a sacred chest constructed during the Israelites’ desert wanderings (Exodus 25). Built of acacia wood overlaid with gold, it contained:

- The stone tablets of the Ten Commandments

- Aaron’s rod (symbol of legitimate authority)

- A jar of manna (symbol of provision and dependence)

What the Ark Contained — and Why Each Item Matters Psychologically

The Stone Tablets (Law)

The tablets represent externalized moral reality, or principles that do not originate in personal preference, mood, or power. Psychologically, this matters because humans require something outside themselves to organize conscience.

Without an external moral reference:

- Authority collapses into narcissism

- Rules become negotiable under stress

- Power becomes self-justifying

This aligns with Carl Jung’s observation that when the ego replaces the symbolic moral order, archetypal forces erupt unconsciously, often in destructive form (Jung, 1959).

In family systems, this shows up when parents change rules depending on emotional state. In institutions, it appears as “policy drift.” The tablets symbolize that ethical reality must be held somewhere stable, not improvised moment to moment.

Aaron’s Rod (Legitimate Authority)

Aaron’s rod is not just authority, it is legitimized authority. It signifies leadership that is recognized, not seized.

Psychologically, this distinction parallels family-systems theory: authority that is calm, predictable, and role-based stabilizes systems, while authority fused with anxiety destabilizes them (Bowen, 1978).

In institutions, Aaron’s rod represents leadership derived from role, accountability, and ethical alignment, not charisma or coercion, which is an insight echoed by structural family therapist Salvador Minuchin, who emphasized that unclear or inflated authority leads to systemic collapse (Minuchin, 1974).

The Jar of Manna (Dependency and Limits)

Manna could not be hoarded. It spoiled when stored improperly.

This is a profound psychological statement:

Provision is real, but control is limited.

In trauma psychology, compulsive hoarding, for example, emotional, relational, or material, is often a response to past deprivation (van der Kolk, 2014). The manna teaches sufficiency rather than excess, reminding us that systems must be designed around enoughness, not endless accumulation.

The Ark was housed in the Holy of Holies, carried only under strict conditions, never touched directly, and approached with reverence. Above it sat the mercy seat, flanked by two cherubim, symbolizing that law itself must be mediated by something greater than punishment alone.

Historically, the Ark traveled with the people. It was not a static monument of empire, but a portable center of meaning. After the destruction of the First Temple (586 BCE), the Ark disappears from the historical record, thereby giving rise to theological, symbolic, and psychological interpretations that persist to this day.

Makeda, Solomon, and Menelik: Lineage, Transfer, and the Ethics of Power

According to the Kebra Nagast, the Queen of Sheba, or Makeda, visited Solomon, drawn by wisdom rather than wealth. Their son, Menelik I, returns to Ethiopia with the Ark itself.

Psychologically, this story encodes ethical succession: power that survives must be transferred, not seized. This mirrors family-systems research by showing that unresolved power struggles across generations produce anxiety, rigidity, and collapse (Bowen, 1978).

The Ark is entrusted, not conquered, reframing authority as inheritance with responsibility, not dominance.

The Ark as Psychological Container

Containment is the capacity to hold what is overwhelming, such as emotion, power, memory, and, without discharging it destructively. Trauma research consistently demonstrates that uncontained experience leads to dysregulation, reenactment, and harm (Herman, 1992).

The Ark:

- Holds law rather than weaponizing it

- Restricts access rather than encouraging domination

- Requires process, mediation, and reverence

Jung described such symbolic containers as essential for mediating archetypal forces safely (Jung, 1969). The Ark is not power itself.

It is the structure that makes power survivable.

Law Held Within Relationship: Covenant, Not Control

Law without relationship becomes authoritarian.

Relationship without structure becomes chaotic.

Covenant integrates both.

This principle is foundational in attachment theory and family systems: safety emerges when boundaries and connection coexist (Minuchin, 1974; Bowlby, 1988).

Mythologist Joseph Campbell argued that enduring myths teach societies how to align with power without being consumed by it (Campbell, 1949). The Ark does exactly this.

The Mercy Seat: Regulation above Judgment

Judgment is not removed. Law remains intact.

But mercy regulates law.

Neurobiologically, shame and fear shut down integration, while compassion paired with boundaries enables growth (Siegel, 2012). Trauma-informed systems therefore preserve consequences while prioritizing repair (Herman, 1992).

The Ark’s design insists that authority must restrain itself.

Power that Cannot be Possessed

The Ark represents non-appropriable power.

Jung warned that identification with archetypal authority produces psychological inflation, or an ego swollen beyond human limits (Jung, 1959). Inflated authority cannot tolerate dissent and confuses challenge with threat.

Historian Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi observed that civilizations survive not by possessing the past, but by bearing it responsibly (Yerushalmi, 1982).

Collective Memory and Portable Identity

The Ark travels.

It anchors identity during displacement.

Trauma fractures memory; symbols restore narrative continuity (van der Kolk, 2014). Healthy systems preserve meaning without rigidity and memory without reenactment.

Family Systems: Why Uncontained Families Collapse

Family-systems research consistently shows that systems fail when authority is unregulated, boundaries are punitive or absent, and trauma is exposed without containment (Bowen, 1978; Minuchin, 1974).

The Ark teaches that containment precedes healing.

Leadership, Ethics, and Institutional Design

Institutions fail not because they lack compassion but because they lack containment.

Trauma-informed institutional design requires:

- Clear authority structures

- Transparent accountability

- Ethical constraints on leadership

- Mechanisms for repair

Without these, organizations reenact trauma at scale (Bloom & Farragher, 2013).

Conclusion: The Ark as a Blueprint for Dignified Systems

The Ark of the Covenant endures not because it was powerful but because it taught how to hold power safely. Unless power is contained, it will consume the very people it claims to protect.

Sources:

- Bloom, S. L., & Farragher, B. (2013). Restoring Sanctuary. Oxford University Press.

- Bowlby, J. (1988). A Secure Base. Routledge.

- Bowen, M. (1978). Family Therapy in Clinical Practice. Jason Aronson.

- Campbell, J. (1949). The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Princeton University Press.

- Herman, J. (1992). Trauma and Recovery. Basic Books.

- Jung, C. G. (1959). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Princeton University Press.

- Jung, C. G. (1969). Psychology and Religion. Yale University Press.

- Minuchin, S. (1974). Families and Family Therapy. Harvard University Press.

- Siegel, D. J. (2012). The Developing Mind. Guilford Press.

- van der Kolk, B. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score. Viking.

- Yerushalmi, Y. H. (1982). Zakhor: Jewish History and Jewish Memory. University of Washington Press.